Discovery of a tyrannosaurus rex skull in montana

by Kelly Milner Halls

Highlights for Children, April 1998

To find the fossilized bones of a Tyrannosaurus rex, where -- exactly -- do you look?

Paleontologists know T. rex fossils can be found in the badlands of the western United States and Canada. Diggers have discovered skeletons of the "tyrantlizard king" there before. But the badlands cover a huge area.

Scientists at the Geology Museum of the University of Wisconsin at Madison were lucky. In 1992, a clue was dropped into their laps.

That clue came from a businessman named Peter Helland. In 1975 he made a long hike across Montana, under a hot sun that scorches the badlands every summer.

Around him rose giant flat-topped hills called buttes. (Buttes rhymes with mutes.) The hills were made of layers of rock. Some had the stairstep look of a wedding cake.

These hills were formed during millions of years. First, many rivers and streams laid down their mud and sediment, which turned into great sheets of rock thousands of miles across. Within that rock, a few plants and animals were preserved as fossils.

Then, the area became dry and barren. In the past few thousand years, cloudbursts have created flood waters that cut deep ravines and left buttes standing here and there.

Fossil clues to the past are recorded in the sides of the buttes. The record goes back to the time of the dinosaurs, when this barren place was a riverbed visited by Triceratops, T. rex, and other prehistoric creatures.

Scattered Fossils

Peter Helland spotted several bones scattered across the foot of an eroded butte. Flood waters had freed the bones from the rock and washed them down the hill. Mr. Helland took some of the bones as souvenirs. For seventeen years, he kept them locked away.

In early 1992, the Geology Museum invited rock collectors to bring in their treasures for identification. Mr. Helland asked the experts to tell him what he had found.

"He emptied the bag, and the first thing to spill out was this incredible toe bone of a Tyrannosaurus rex," said Craig Pfister, a paleontologist at the museum.

Mr. Pfister, Chris Pladziewicz, and their team were excited about the bone. Since the first T. rex was discovered in 1900, only twenty-three T. rex skeletons have been found. Fifteen of them were discovered in the past fifteen years. Most of them were less than half complete.

Mr. Helland's find pointed the way for the museum's next fossil search. In the summer of 1992, Mr. Pfister and the university dig team hunted T. rex fossils in the same badlands of Montana.

Scattered across the buttes were fragments of cream-colored dinosaur fossils -- guideposts to bigger discoveries.

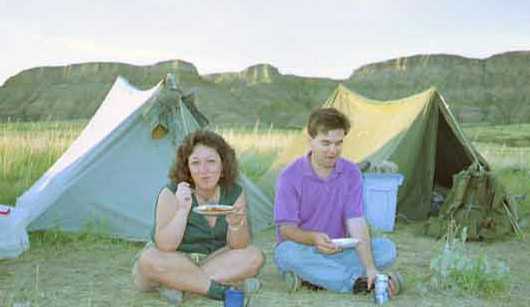

The team hiked, scanning the ground, looking for fossils of T. rex. Carrying canteens, tools, and backpacks, they slid down miles of flood-carved ravines. Beyond the ravines, they scaled slippery buttes. In the dry heat, they guzzled gallons of warm water to fight off dehydration.

During two summers, they found enough Triceratops fossils to piece together a nearly complete skeleton. But they did not find a single sign of Mr. Helland's' T. rex.

The Skull

In 1994, Mr. Pfister left camp to explore the fossil-rich soils of a nearby ranch. He scaled a particularly steep butte, inching his way up the dirt-covered slope, searching for bone.

About a mile up the slope, he spotted a large chunk of light-colored bone peeking out of the mudstone.

It was part of a T. rex skull.

He led his companions to the dig site, where they climbed up the butte to chip away at the stone. At first there was no place to stand or kneel. While they worked, they had to perch like mountain goats on the tiny, steep ridges or lie flat against the slope.

After ten weeks, the six-member team had freed the skull from the rock, and they had carved thirty-five feet into the side of the butte in their search, finding many more T. rex bones.

Half-Ton Package

A big challenge remained -- getting the fossil back down the buttes and ravines. The skull weighed about one thousand pounds.

Some scientists use helicopters to carry the heavy bones from dig sites to trucks or trailers. "We didn't have enough money for that," Mr. Pfister said. "So we used the hood of a 1950 Chevy pickup truck to make a sled, and dragged it out."

It took two days for six members of the paleontology team and several ranch hands to drag the massive skull and other bones back to camp.

Today, almost four years later, most of the skull is still encased in stone. "The skull is crusted over with an inch or more of hard iron oxide," said the Geology Museum director, Dr. Klaus Westphal. "That's like being wrapped in iron."

Now the scientists are working with an expert who is developing new ways to remove hard rock from fragile fossils.

Soon, we will be able to see a new view of the tyrant.

COPYRIGHT 1998 Highlights for Children, Inc.

Highlights for Children, April 1998

To find the fossilized bones of a Tyrannosaurus rex, where -- exactly -- do you look?

Paleontologists know T. rex fossils can be found in the badlands of the western United States and Canada. Diggers have discovered skeletons of the "tyrantlizard king" there before. But the badlands cover a huge area.

Scientists at the Geology Museum of the University of Wisconsin at Madison were lucky. In 1992, a clue was dropped into their laps.

That clue came from a businessman named Peter Helland. In 1975 he made a long hike across Montana, under a hot sun that scorches the badlands every summer.

Around him rose giant flat-topped hills called buttes. (Buttes rhymes with mutes.) The hills were made of layers of rock. Some had the stairstep look of a wedding cake.

These hills were formed during millions of years. First, many rivers and streams laid down their mud and sediment, which turned into great sheets of rock thousands of miles across. Within that rock, a few plants and animals were preserved as fossils.

Then, the area became dry and barren. In the past few thousand years, cloudbursts have created flood waters that cut deep ravines and left buttes standing here and there.

Fossil clues to the past are recorded in the sides of the buttes. The record goes back to the time of the dinosaurs, when this barren place was a riverbed visited by Triceratops, T. rex, and other prehistoric creatures.

Scattered Fossils

Peter Helland spotted several bones scattered across the foot of an eroded butte. Flood waters had freed the bones from the rock and washed them down the hill. Mr. Helland took some of the bones as souvenirs. For seventeen years, he kept them locked away.

In early 1992, the Geology Museum invited rock collectors to bring in their treasures for identification. Mr. Helland asked the experts to tell him what he had found.

"He emptied the bag, and the first thing to spill out was this incredible toe bone of a Tyrannosaurus rex," said Craig Pfister, a paleontologist at the museum.

Mr. Pfister, Chris Pladziewicz, and their team were excited about the bone. Since the first T. rex was discovered in 1900, only twenty-three T. rex skeletons have been found. Fifteen of them were discovered in the past fifteen years. Most of them were less than half complete.

Mr. Helland's find pointed the way for the museum's next fossil search. In the summer of 1992, Mr. Pfister and the university dig team hunted T. rex fossils in the same badlands of Montana.

Scattered across the buttes were fragments of cream-colored dinosaur fossils -- guideposts to bigger discoveries.

The team hiked, scanning the ground, looking for fossils of T. rex. Carrying canteens, tools, and backpacks, they slid down miles of flood-carved ravines. Beyond the ravines, they scaled slippery buttes. In the dry heat, they guzzled gallons of warm water to fight off dehydration.

During two summers, they found enough Triceratops fossils to piece together a nearly complete skeleton. But they did not find a single sign of Mr. Helland's' T. rex.

The Skull

In 1994, Mr. Pfister left camp to explore the fossil-rich soils of a nearby ranch. He scaled a particularly steep butte, inching his way up the dirt-covered slope, searching for bone.

About a mile up the slope, he spotted a large chunk of light-colored bone peeking out of the mudstone.

It was part of a T. rex skull.

He led his companions to the dig site, where they climbed up the butte to chip away at the stone. At first there was no place to stand or kneel. While they worked, they had to perch like mountain goats on the tiny, steep ridges or lie flat against the slope.

After ten weeks, the six-member team had freed the skull from the rock, and they had carved thirty-five feet into the side of the butte in their search, finding many more T. rex bones.

Half-Ton Package

A big challenge remained -- getting the fossil back down the buttes and ravines. The skull weighed about one thousand pounds.

Some scientists use helicopters to carry the heavy bones from dig sites to trucks or trailers. "We didn't have enough money for that," Mr. Pfister said. "So we used the hood of a 1950 Chevy pickup truck to make a sled, and dragged it out."

It took two days for six members of the paleontology team and several ranch hands to drag the massive skull and other bones back to camp.

Today, almost four years later, most of the skull is still encased in stone. "The skull is crusted over with an inch or more of hard iron oxide," said the Geology Museum director, Dr. Klaus Westphal. "That's like being wrapped in iron."

Now the scientists are working with an expert who is developing new ways to remove hard rock from fragile fossils.

Soon, we will be able to see a new view of the tyrant.

COPYRIGHT 1998 Highlights for Children, Inc.